A Short Proof of Brickman's Theorem

This was based on a conversation with Alex Wang and Mark Gillespie. Alex has a blog post about Dine’s theorem, which is very related to this theorem.

There are a lot of places in algebraic geometry where convexity appears in surprising places. One well known result coming from quadratic programming is a theorem of Brickman.

Theorem (Brickman)

Let $n \ge 2$. Let $Q_1, Q_2$ be homogeneous quadratic maps on $\mathbb{R}^{n+1}$, and let $Q : \mathbb{R}^{n+1} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$ be given by $Q(x) = (Q_1(x),Q_2(x))$. Let $S^{n} = \{x \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1} : |x|_2 = 1\}$. Then $Q(S^{n}) \subseteq \mathbb{R}^2$ is convex.

There are a few well known proofs of this theorem (see for example, Barvinok’s A Course on Convexity), which tend to involve passing to some associated convex set of positive semidefinite matrices, and then showing that the image of that convex set under a linear projection agrees with the image of the sphere under these quadratic maps.

Our goal is to give a short, geometric proof of this fact, which uses only some elementary observations.

Proof

We base our proof on two facts:

-

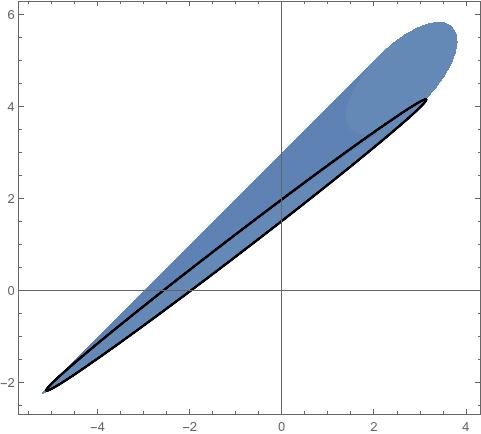

The image of the unit circle $S^1 = \{(x,y) : x^2+y^2 = 1\}$ under a homogeneous quadratic map $Q : \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n$ is also the image of the unit circle under an affine map. We will call the image of $S^1$ under an affine map an ellipse. We prove this below the fold.

Click to expand

This surprising geometric fact is the main reason the result holds. To see why it is the case, notice that each point on the circle can be written as $(\cos(t), \sin(t))$, and that any homogeneous quadratic function $a\cos(t)^2 + b \cos(t) \sin(t) + c\sin(t)^2$ can be expressed as a linear combination of the functions $\cos(2t)$, $\sin(2t)$ and 1. This implies that if we apply a quadratic function to the unit circle, the image can be parameterized as $v_1 \cos(2t) + v_2 \sin(2t) + v_3$ for some $v_1, v_2, v_3 \in \mathbb{R}^n$, and it is therefore the image of $S^1$ under the affine map $(x,y) \mapsto v_1 x + v_2 y + v_3$.

-

If $X$ is a simply connected topological space (for example $S^{n}$ for $n \ge 2$), $\gamma$ is a closed curve in $X$, and $f : X \rightarrow Y$ is a continuous map, then the image of $\gamma$ is contractible in the image of $f$.

With these facts, we can show the result.

Let $a = Q(x)$, and $b = Q(y)$, where $x, y\in S^n$. We want to show that the line segment from $a$ to $b$ is in the image of $S^n$ under $Q$.

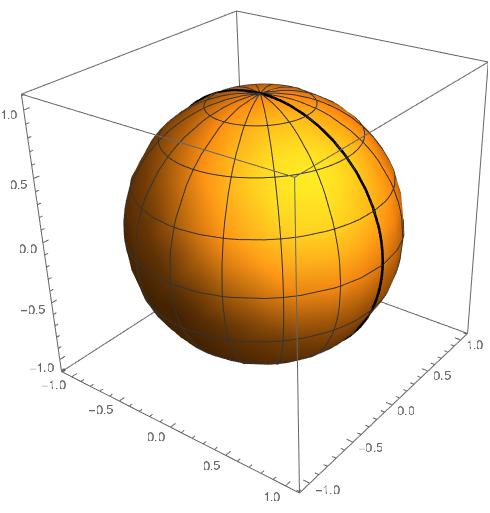

Consider the great circle from $x$ to $y$ in $S^n$, which is the image of $S^1$ under the linear map $(u,v) \mapsto u \hat{x} + v \hat{y}$, where $\{\hat{x}, \hat{y}\}$ is an orthonormal basis for the linear span of $x$ and $y$. Now, if we compose $Q$ with this linear map from $S^1$, we obtain a quadratic map from $S^1$ to $\mathbb{R}^2$, whose image we have seen is an ellipse, which contains both $a$ and $b$.

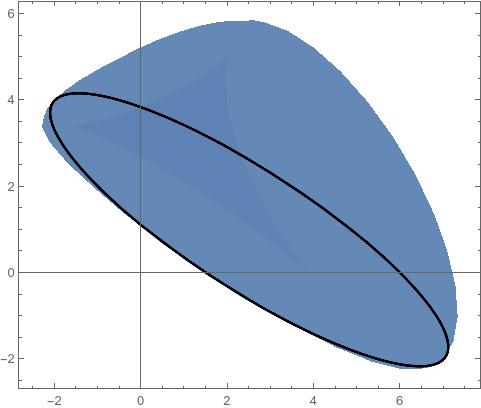

The ellipse divides $\mathbb{R}^2$ into two pieces: the compact inside part, and the unbounded outside part. The compact inside part is convex, and therefore, it contains the line segment from $a$ to $b$. Because the $S^{n}$ is simply connected, it must be the case that every point in the inside part of the ellipse must be contained in the image. (To see this, say that some subset of the inside part of the ellipse is missing from the image, then the ellipse would not be contractible in the image set.)

Therefore, the line segment from $a$ to $b$ is contained in the image, and we are done.

A Great Circle on the Sphere. The image of a sphere with a special great circle highlighted.