Braid Codes

The fields of information theory and group theory intersect in a wide variety of places; finite fields are fundamental in the development of error correcting codes, and groups appear in a number of encryption schemes. I wanted to sketch another connection between source codes and general monoids.

This is a project that I worked on for the course math 7018, Fall 2020. Source image is from here.

Source Codes and Monoids

Basics of Coding Theory

The basic goal in Source information theory is to represent a collection of states using symbols in as efficient a way as possible. It is clear that the total number of symbols required to represent a collection of $k$ state is at least $k$. As an example, a stop sign has 3 possible states, either red green or yellow, and this is enough to convey whether a person should stop, slow or go. To communicate more information, like whether turning left is allowed, more symbols are needed.

To represent a possibly infinite number of states, one typically writes down a sequence of characters coming from some fixed alphabet, and in doing this, one typically wants to represent those states using as few characters as possible. As an example, each English word is represented as a sequence of characters from the fixed 26 character alphabet, and each English sentence is represented as a sequence of words from a fixed 200 thousand word dictionary.

In one of the basic problems of coding theory, one is interested in representing a sequence of characters from one alphabet in terms of a second alphabet. A typical example of this is ASCII encoding: most English text is composed of a sequence of about characters from a 200 character alphabet; in order to record a text in binary, one needs to represent each of these characters as a binary string. To represent about 200 characters, one needs at least 8 binary characters per English character, and indeed, this is the length of the representation of every English character in ASCII. In a sense, we are trying to simulate a full English alphabet of 26 characters using only 2 characters at a time.

In mathematical terms, we have some collection of states $X$, which we want to represent, and a base alphabet $A$. To each state $x \in X$, we want to assign an encoding $\phi(x) \in A^*$, where $A^*$ is the set of all strings made using the alphabet $A$. If our base alphabet $A$ consists of $n$ characters, we can represent $n^k$ possible states with $k$ character strings from $A$, so if all states in $X$ have representations of the same length in $A$, each character in $X$ needs to have an encoding of length at least $\log_n(X)$. If $X$ is itself a set of strings over some alphabet $B$, so that $X = B^*$, then we would also like the encoding to preserve the concatenation operation, i.e. if we have two characters in $X$, $a, b \in X$, and we form the string $ab$, we want $\phi(ab) = \phi(a) + \phi(b)$.

Variable Length Codes

The ASCII encoding is nice because each character’s encoding has the same length; this makes it relatively easy to read an ASCII encoded string, you simply break the string into 8 character chucks, turn each chunk into a Latin character. However, this encoding is somewhat wasteful. Notice that the character e has the same length as the character q, even though e appears significantly more often in English than q does. For example, consider the opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” The letter e appears 5 times, whereas q does not appear at all. Imagine a code where e was represented by 7 characters, and q was represented by 9; for almost all text, this would result in a savings in terms of the number of bits needed to express them.

Nowadays, when bits are plentiful, we do not care so much about these minor savings, but back when people used telegrams, they cared a lot more. So for example, in Morse code, e takes up only 1 dot, whereas q takes up 4. This means that it is a lot faster to transmit e than to transmit q, which in practice is good, because you want to transmit an e a lot more often.

So, say we have finite alphabets $B$ and $A$, and want an encoding $\phi : B^* \rightarrow A^$. In order for this code to be usable, it had better be the case that different elements of $B^$ map to different elements of $A^*$. For example, if we had an encoding that looked like

\begin{align} a \rightarrow 011\ b \rightarrow 101\ c \rightarrow 01 \end{align}

then the strings cb and ac would be encoded by the same string 01101. If we try to decode this string, we would be faced with ambiguity.

A code where each encoded string has exactly one decoding is called uniquely decodable. This is the same as saying the map $\phi : B^* \rightarrow A^*$ is injective.

In practice, the goal is to find a code that minimizes the average length of a codeword, when the characters are drawn from a fixed distribution, like that of the English language. The uniquely decodable assumption puts constraints that make it difficult to make the code short. For example, we cannot give each character in the alphabet the code 0, even though that would make all of the codewords very short, because that would make it impossible to retrieve the information from the code. Intuitively, if we try to make the codewords too short, then for a large alphabet $B$, the codewords will have to start colliding when you concatenate a lot of characters together.

The formal bound expressing the intuition that short codes are difficult to create is known as Kraft’s inequality.

Lemma 1

Suppose that we have a uniquely decodable code $\phi : B^* \rightarrow A^*$, and that $|A| = n$. Use $|s|$ to denote the length of a string in $s \in B^*$. $$ \sum_{b \in B} n^{-|\phi(b)|} \le 1 $$

The proof of Kraft’s inequality for uniquely decodable codes is one of my favorite proofs, and we’ll do it in slightly greater generality in a moment.

As a slight abuse of language, if we have some numbers $\ell_i$, then we say that $\ell_i$ satisfies Kraft’s inequality if $$ \sum_{i \in A} n^{-\ell_i} \le 1 $$ It is a theorem that if $\ell_i$ satisfy Kraft’s inequality, then there is in fact a uniquely decodable code so that $|\phi(i)| = \ell_i$.

Relations in monoids

We now want to generalize some of our previous observations about codes. We say that a set $M$ is a monoid if there is a binary operation $\cdot : M \times M \rightarrow M$ so that $a \cdot (b \cdot c) = (a\cdot b)\cdot c$, and for some $e \in M$, $e \cdot m = m$ for all $m \in M$. If we have two monoids, $M_1$ and $M_2$, a map $\phi : M_1 \rightarrow M_2$ is said to be a homomorphism if $\phi(a\cdot b) = \phi(a) \cdot \phi(b)$.

The easiest example of a monoid is probably the free monoid over a set $B$, $B^*$, where the set consists of all strings of characters in $B$, and the binary operation is string concatenation. We can reformulate our previous language as follows: a code is a monoid homomorphism between two free monoids, and a code is uniquely decodable if and only if that monoid homomorphism is injective.

All monoids can be thought of in terms of sequences of strings, but where some of the strings are considered to be equivalent. In a free monoid, if we write down one sequence of strings $x_1x_2\dots x_n$, and someone else writes down another sequence $y_1y_2\dots y_m$, then these two strings are equal if and only if $m = n$ and $x_i = y_i$ for each $i$ from 1 to $n$. This is pretty obviously something you can do this when dealing with binary strings, but we might be interested in slightly more exotic examples of monoids.

A classic example of this difficulty is Russian cursive: it is famously difficult to read Russian cursive, because many of the characters look the same.

In particular, it is very difficult, for foreigners like myself, when there are strings of similar appearing characters. We call such a thing a relation between characters.

A monoid (not necessarily free) is like the set of strings in some alphabet, but written down using very bad handwriting, so that some strings are indistinguishable from others, even though they might have been made by different characters. Nevertheless, Russians continue to write in cursive, and they are able to have a functioning society, indicating that it should still be possible to represent information using such an alphabet.

To do this, we want to understand the notion of source coding in a more general setting. Technically, in a general monoid, we do not have a notion of how “long” an element of the monoid is, because we cannot tell which strings are supposed to be length 1. Because of that, we will actually want our monoid $A$ to be finitely presented, meaning that we can write it in the following form: $$ A = \langle a_1, a_2, \dots, a_n | s_1 = t_1, \dots, s_k = t_k\rangle $$ where $a_1, \dots, a_n \in A$, and $s_1,t_1 \dots, s_k, t_k \in A^*$.

This denotes the fact that every element in $A$ can be written as a product of characters $a_1, \dots, a_n$, but that the strings $s_i$ and $t_i$ are identified for each $i$. Given such a presentation, we can simply declare every generator to have length 1, and then declare the length of any element $x \in A$ to be minimum length of a string of generators resulting in $x$. In this case, we denote the length of $x$ by $|x|$.

Now, if $B$ is a finite alphabet, and $M$ is a finitely presented monoid, then a code for $B$ over $M$ is a monoid homomorphism $\phi$ from $B^*$ to $M$, and that code is said to be uniquely decodable if $\phi$ is injective. The length spectrum of a code $\phi$ is the list $(|\phi(b)|)_{b \in B}$.

We are interested in codes whose length spectrum is “small” in some sense, but once again, we might suspect that being uniquely decodable poses some restrictions on the length spectra on codes. In particular, if the length spectrum of $\phi$ consists of only small numbers, then there must be `a lot’ of short elements of $M$.

Formally, let $ M_k = {m \in M : |m| = k}$ be the set of all monoid elements of length $k$. There is a generalized Kraft inequality, given as follows:

Theorem 1

Let $M$ be a monoid, and let $\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$ be any number so that $|M_k| = O(\alpha^k)$ for all $k \ge 0$. Let $\phi : B^* \rightarrow M$ be a uniquely decodable code, then $$ \sum_{b \in B} \alpha^{-|\phi(b)|} \le 1. $$

Proof

We think of $g$ in the following expression to be a type of generating function for the lengths of encoded characters. $$ g = \sum_{b \in B} \alpha^{-|\phi(b)|} $$ Then take $g^{\ell}$ for some $\ell \in \mathbb{N}$. We can expand this out to be a sum over all strings in $B$: $$ g^{\ell} = \sum_{b_1 b_2\dots b_{\ell} \in B^*} \alpha^{-(|\phi(b_1)| + \dots + |\phi(b_{\ell}|)} $$

Notice that $|\phi(b_1)| + \dots + |\phi(b_{\ell})|$ is an upper bound for $|\phi(b_1+\dots+b_{\ell})|$. Thus, $$ \sum_{b_1, b_2,\dots,b_{\ell} \in B} \alpha^{-(|\phi(b_1)| + \dots + |\phi(b_{\ell})|)} \le \sum_{b_1, b_2,\dots,b_{\ell} \in B} \alpha^{-(|\phi(b_1+\dots + b_{\ell})|} $$

Let $L_i = {s \in B^* : \phi(s) \in M_i}$. First, note that $\phi$ is injective, so $|L_i| \le |M_i| = O(\alpha^i)$.

Next, we reindex this summation to first sum over $i$: $$ g^{\ell} = \sum_{i=1}^{\ell \max_{b \in B} |\phi(b)|} |L_i| \alpha^{-i} \le \sum_{i=1}^{\ell \max_{b \in B} |\phi(b)|} \alpha^i O(\alpha^{-i}) $$ Where we have used the upper bound that any string of length $\ell$ in $B^*$ maps to a string of length at most $\ell \max_{b \in B}|\phi(b)|$. Hence, $$ g^{\ell} \le O((\max_B |\phi(b)|)\ell). $$ Note, if $g > 1$, then $g^{\ell}$ grows exponentially for large $\ell$, yet the right hand side grows only linearly in $\ell$. So for $\ell$ large enough, this inequality could not hold. Thus, $g \le 1$, and this concludes the proof.

One somewhat remarkable aspect of Kraft’s inequality is that it only uses asymptotic information about growth rate of elements in a monoid, yet, the result is fully quantitative.

Next, we will seek to apply this inequality in the case of a very special class of monoids: namely the monoid of braids.

Braids

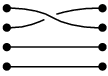

One type of monoid, whose structure has been studied in depth in the field of topology, is the braid monoid. We think of a braid as a collection of strings, with fixed endpoints, which have been tangled with each other in some complicated way.

Formally, a braid on $n$ strands is a collection of $n$ paths $p_i : [0,1] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$, where there exists a permutation $\pi \in S_n$, so that $p_i(0) = (i, 0, 0)$, $p_i(1) = (\pi(i), 0, 1)$, and for each $t$ and $i$, $p_i(t)_3 = t$. We consider two braids to be equivalent of one can be continuously deformed into the other. The permutation involved in the definition is crucial, and we will denote by $p(b)$ the underlying permutation of a braid $b$.

We will say that a braid is positive if each time $p_i(t)_1 = p_j(t)_1$, and $i > j$ we have that $p_i(t)_2 > p_j(t)_2$. That is to say, that each crossing of strands in the braid has the left strand crossing over the right one. Thus, a positive braid can be represented as a 2 dimensional picture, where we forget about the second coordinate.

This collection of braids turns into a monoid via concatenation, where we concatenate each of these paths with each other, say by letting

$$(r\cdot q)_i(t) = \begin{cases} r_i(\frac{t}{2}) & \text{ if }t \le \frac{1}{2} \\ q_{{p(r)(i)}}(\frac{t}{2} + \frac{1}{2}) & \text{ if } t \ge \frac{1}{2}\end{cases}.$$

We will use the braid monoid to refer to the monoid of positive braids, as this will be the main object of our study.

There is a natural monoid homomorphism that sends the braid monoid to the symmetric group which sends each braid to the permutation of the endpoints that it induces.

Despite the fact that this definition of the braid monoid is continuous in nature, the braid monoid is in fact finitely presented. The Artin presentation for the positive braid monoid is given by $$\langle \sigma_i | \sigma_i \sigma_j = \sigma_j \sigma_i \text{ if } |i-j| > 1\text{ and }\sigma_i\sigma_{i+1}\sigma_i = \sigma_{i+1}\sigma_i\sigma_{i+1}\rangle$$ Geometrically, the generator $\sigma_i$ represents the operation of twisiting strands $i$ and $i+1$. The relations reflect basic operations that one can do on the level of braids which preserve homotopy equivalence. (See for example \cite{gonzalez2011basic}).

Codes over the braid monoid have an appealing physical interpretation: if we had a code $\phi : X^* \rightarrow B_n$ one can imagine taking $n$ strands of string and braiding them together to encode messages in the alphabet $X$. As an example, it is not hard to see that if we take $X = {0, 1}$, and let $\phi(0) = \sigma_1$ and $\phi(1) = \sigma_2$, we would get a uniquely decodable binary code, and we could encode binary strings as braids. This shows that if $n > 3$, braids allow for representations that are at least as efficient as simple binary codes. Can we do better?

Kraft’s inequality indicates that we should begin by considering the growth rate of the braid monoid. This is the subject of much study, and has been completely solved in the most important of cases. We will recount the details of this study here, which show, somewhat surprisingly, that in fact the growth rate of all braid codes is bounded from above by a constant. This implies that while it is possible to obtain codes which are more efficient than binary codes using braids, it is not possible to be more efficient than a 4 character alphabet.

Also, the study the structure of which elements in a braid monoid generate a free monoid is well studied, but difficult, indicating that there is still much to learn in this field.

Growth Rates of Braid Codes

Let $M = B_n$ be the braid monoid on $n$ strands, together with the Artin presentation given above. Let $M_k$ be the set of elements of $M$ with length $k$. The growth function of $M$ is defined to be $$g_M(t) = \sum_{i=0}^{\infty}|M_k| t^k$$

This is a generating function for the number of elements of size $k$ in $M$.

A result of Deligne that this growth function is in fact rational (indeed, it is the reciprocal of a polynomial).

We will first give a proof of this fact (found in \cite{epstein1992word}) in terms of the so called `automatic structure’ of the braid monoid, as it will set up some interesting further questions related to alternative presentations of the braid monoid, and it will also give a taste of some of the proof techniques used in this field.

Then, we will give a more detailed examination of the growth function of the braid codes using the results in \cite{flores2018growth}. This will initially rely intimately on the so-called Garside structure for the braid monoid.

Automatic Monoids

The results described in this section are found in \cite{epstein1992word}

For our purposes, a finite automaton $F$ is a triple $(X, G, \ell, v_0)$, defined as follows. $X$ is some finite alphabet, and $G$ is a directed graph (possibly with parallel edges and loops). $\ell : E(G) \rightarrow X$ is a labelling of the edges of $G$, so that for each vertex $v \in G$, and $x \in X$, there is at most one directed edge incident to $v$ with the label $x$. $v_0$ is some distinguished vertex of $G$.

We will think of this kind of finite automaton as being a simplified model of computation. A string $w = w_1w_2\dots w_n$ is accepted by $F$ if there is a walk $v_0, v_1, \dots, v_n$ in $G$ so that $\ell(v_i, v_{i+1}) = w_{i+1}$ for each $i \in {0, \dots, n}$. Such a walk, if it exists, is unique. (As a note, we think of strings in this context as being terminated by a special character that signals that the string has ended. This does not impact the counting applications that we describe next.)

The regular language defined by $F$ is defined to be the set of strings which are accepted by $F$. A set of strings is said to be a regular language if it is accepted by some finite automaton.

For our counting related purposes, we will consider a finitely presented monoid $M$, generated by elements $g_1, \dots, g_k$, to be automatic if there is a regular language $L$ with alphabet ${g_1, \dots, g_k}$, with the property that the map $f : L \rightarrow M$ given by sending $w_1 w_2 \dots w_n \in L$ to the product $w_1\cdot w_2 \dots w_n$ is bijective. In this case, for any $b \in M$, we say that $f^{-1}(b)$ is the canonical word representing $b$. In the literature, there are some additional requirements for being automatic, which are defined in \cite{epstein1992word}.

The key fact which is relevant for counting purposes is that the growth rate of a regular language is highly constrained:

Lemma 2

If $L$ is a regular language, and we let $L_k$ be the set of elements of $L$ of length $k$, then $$ g(t) = \sum_{i=0}^{\infty} |L_k|t^k $$ is the reciprocal of a polynomial.

Proof

Let $F$ a finite automaton recognizing $L$. The number of strings of length $k$ in $L$ are in bijection with walks in $G$

We can count such walks in terms of $A$, the adjacency matrix of $G$ . Indeed, if $A$ is this adjacency matrix, then the number of walks from $v_0$ to $v’$ of length $k$ is $A^k_{v_0, v’}$. Thus, $$ |L_k| = \sum_{v’ \in V(G)} A^k_{v_0, v’} = f(A^k) $$ where crucially, $f$ is linear. Hence, we see that $$ g(t) = f(\sum_{i=0}^{\infty} (At)^k) = f(\frac{1}{1-At}) $$ The entries of $\frac{1}{1-At}$ are all rational functions of $t$, and so, we are done.

This is especially useful for computing growth rates.

Lemma 3

If $g(t) = \sum_{k \ge 0}a_k t^k$ is the reciprocal of a polynomial, then there is a constant $c$ so that $M_k = \Theta(poly(k) c^k)$, where $c$ is smallest norm of all of the roots of $\frac{1}{g(t)}$.

Thus, for an automatic monoid, the growth function is rational. The motivation for considering automatic monoids should be clear:

Lemma 4

The positive braid monoid is automatic.

The formal proof is given in \cite{epstein1992word}. The proof of this theorem requires some ideas that are relevant to the Garside theory of the braid monoid (which is also useful for doing computations with the braid monoid).

Firstly, we need the notion of a simple braid. A positive braid $b$ is simple if for pair of strands crosses at most once. We can imagine that if the $b$ induces a permutation $\pi$, that the strand starting from the $i^{th}$ starting point goes directly to the the $\pi(i)^{th}$ ending point without becoming entangled with any other strands. As it turns out the map $p$ sending a braid $b$ to its induced permutation restricts to a bijection on simple braids. Thus, for fixed $n$, there are $n!$ simple braids.

Positive braids are ordered under the prefix ordering, under which $b_1 \prec b_2$ if there is some positive braid $a$ so that $ab_1 = b_2$. The perhaps surprising thing about this ordering is that it forms a lattice; this implies that for any $b_1, b_2$, there is some element $b_1 \lor b_2$ so that if $b_1 \prec a$ and $b_2 \prec a$, then $b_1 \lor b_2 \prec a$. In this ordering, the meet of all simple braids is a special element known as the Garside element of $M$. In this case, the Garside element has a physical meaning: we can imagine taking all of the strands, and then performing a full twist, reversing the ordering of the strands. This lattice structure, together with this Garside element, produces a so-called Garside structure on the monoid of positive braids.

We can now sketch a proof that the braid monoid is automatic.

Proof

For each simple braid $s$, assign an arbitrary word $\overline{s}$ representing that braid to be its canonical form.

Once we have canonical words for each simple braid, we can produce a canonical form of each braid, known as the left-greedy form of the braid. In this form, we write $$b = d_1d_2\dots d_k,$$ where each $d_1$ is simple and satisfies the following condition: $d_k$ is the maximal simple braid so that $d_k \prec b$, and if $b = ad_k$, then $d_{k-1}$ is the maximal simple braid so that $d_{k-1} \prec a$, and so on. Note that at each step, this maximal braid exists, due to the lattice structure.

It turns out that in order for a word to be in left-greedy form, it suffices for $d_i$ and $d_{i+1}$ be compatible (in a sense we do not specify) for each $i$, and for each $d_i$ to be written in its canonical form.

Now, we need to recognize the string in right greedy form. We want to read a string from left to right and find where the `breaks’ are between consecutive $d_i$, and also verify that each subsequent $d_i$ are compatible with the previous one.

Hence, let $G$ be the graph whose vertices are pairs of the form $(s_{curr}, s_{next})$, where $s_{curr}$ and $s_{next}$ are simple braids. Our starting vertex is $v_0 = (e, e)$, where $e$ is the identity braid.

We think of $s_{curr}$ as representing $s_i$ for some $i$, and $s_{next}$ as representing the starting part of $s_{i+1}$ in the above decomposition.

On an input character $c$, and at state $(s_{curr},s_{next})$, we make the following transitions: if $s_{next}c$ is a simple braid, then we transition to state $(s_{curr},s_{next}c)$. On the other hand, if $s_{next}c$ is not a simple braid, then we consider a couple cases:

In this case, we would need to show that $s_{next}$ and $s_{curr}$ are compatible, $s_{next}$ is written in its canonical form. If these conditions are not met, then we will fail to transition, and the string will be rejected. If they are met, then we will continue.

This gives a finite automaton recognizing left-greedy form, and we are done.

Computing the Growth Function of Braids

\cite{flores2018growth} offers a more efficient approach to obtaining the growth function for the positive braid monoid in terms of lexicographic representatives.

We will consider the generators of $B_n$ to be ordered, so that $\sigma_1 < \sigma_2 < \dots < \sigma_n$. Given a positive braid $b$, we let the word $w = w_1w_2\dots w_k$ (where each $w_1$ is one of the Artin generators) be the lexicographically first word representing the braid $b$. That is, out of all words $w$ which represent the braid $b$, we choose one where $w_1$ is as small as possible, and out of all such words, we choose one where $w_2$ is as small as possible, and so on.

As it happens, the set of lexicographically first words representing braids is also a regular language, though we will not show this here.

We divide $M$ into pieces depending on what generators appear in the lexicographically first representative of $b$.

Let $$ U^{(i,j)}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i,\dots, \sigma_j \prec b, \sigma_{j+2},\dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$

We see that if $b \in U^{(i,j)}_k$, then the lexicographically first word representing $b$ starts with either $\sigma_j$ or $\sigma_{j+1}$ (since $\sigma_{j}$ divides $b$, and $\sigma_{j+2}$ through $\sigma_{n}$ do not). Moreover, $\sigma_i,\dots, \sigma_j \prec b$ is equivalent to saying that $\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell} \prec b$ from the definition of the meet. Hence, $$ U^{(i,j)}k = \{b \in M_k : \bigvee{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell} \prec b, \text{ the lexicographically first word for }b\text{ starts with }\sigma_j\text{ or } \sigma_{j+1}\} $$

We also define $$ M^{(i)}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_{i+1}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$

A few quick notes: there are two reasons why $U^{(i,j)}$ is of interest. Firstly, $\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}$ is of a simple form: the monoid generated by ${\sigma_{i}, \sigma_{i+1}, \dots, \sigma_{\ell}}$ is isomorphic to a smaller braid monoid (indeed, these generators for the submonoid are precisely the Artin generators for the submonoid). This implies that $\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}$ has the same length as the Garside element for $B_{j - i}$, which has length $\binom{j-i+2}{2}$.

Secondly, we have that for $i \ge j+2$, $\sigma_j$ commutes with $\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}$, which will also be useful for us.

Now, we will relate the $U^{(i,j)}_k$ to $M^{(i)}_k$ in two ways, which will allow us to derive a recurrence relation for $|M^{(i)}_k|$, which will turn allow us to compute $|M_k| = |M^{(n)}_k|$.

Lemma 5

$|U_k^{(i,j)}| = |M_{k - \binom{j-i+2}{2}}^{j+1}|$

Proof

Recall the definition $$ U^{(i,j)}k = {b \in M_k : \bigvee{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell} \prec b, \sigma_{j+2},\dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b} $$ $\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell} \prec b$ if and only if $b = \left( \bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}\right)c$ for some $c$. Moreover, $\left( \bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell} \right) c \in M_k$ if and only if $|c| = k - |\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}|$, where $|\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}| = \binom{j-i+2}{2}$ We will let $m = k - |\bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell}|$.

Also, because $\sigma_{j+2}$ commutes with $\sigma_{\ell}$ for all $\ell \in [i, j]$, and therefore, $\sigma_{j+2}$ divides $\left( \bigvee_{\ell= i }^j \sigma_{\ell} \right) c$ if and only if $\sigma_{j+2} \prec c$. Thus, we have that $$ |U^{(i,j)}k| = |{c \in M_m : a{j+2},\dots, a_n \not \prec c}| = |M_m^{j+1}| $$ as desired

Lemma 6

$|M_{k}^{i+1}| - |M_{k}^{i}| = \sum_{\ell=i}^n (-1)^{\ell - i}|U^{i, \ell}_k|$

Proof

Note that $M_{k}^{i} \subseteq M_{k}^{i+1}$, so that $|M_{k}^{i+1}| - |M_{k}^{i}| = |L_k^i|$, where $$ L_k^i = M_k^{i+1} \setminus M_k^i = {b \in M_k : \sigma_{i} \prec b \text{ and } \sigma_{i+1}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b} $$ Next, note that

$$ U^{(i,i)}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i \prec b\text{ and } \sigma_{i+2}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$

We can divide $U^{(i,i)}$ into those elements where $\sigma_{i+1} \prec b$ and those where $\sigma_{i+1}\not \prec b$, in which case $$ U^{(i,i)}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i \prec b\text{ and } \sigma_{i+1}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} \sqcup \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i, \sigma_{i+1}\prec b\text{ and } \sigma_{i+2}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$ In particular, $L_k^i \subseteq U^{(i,i)}_k$, and we can reason about the set difference.

More generally, applying the same kind of breaking into cases: $$ U^{(i,j)}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i, \dots, \sigma_j \prec b\text{ and } \sigma_{j+1}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} \sqcup \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i,\dots, \sigma_{j+1}\prec b\text{ and } \sigma_{j+2}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$ and

$$ U^{(i,n)}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i,\dots \sigma_n \prec b\} $$

If we let $$ L^{i,j}_k = \{b \in M_k : \sigma_i,\dots \sigma_j \prec b\text{ and } \sigma_{j+1}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$ Then $U^{(i,j)} = L^{i,j}_k \sqcup L^{i,j+1}_k$.

Thus, the sum $$\sum_{\ell=i}^n (-1)^{\ell - i}|U^{i, \ell}k| = \sum{\ell=1}^n (-1)^{\ell - i} (|L^{i, \ell}_k| - |L^{i, \ell+1}_k|) = L^{i}_k$$ which is what we wanted.

The previous two results indicate that there is a linear recurrence amongst the $M_i$:

Lemma 7

$|M_{k}^{i+1}| - |M_{k}^{i}| = \sum_{\ell=i}^n (-1)^{\ell - i}|M_{k - \binom{\ell-i+2}{2}}^{\ell+1}|$

Note that the amount of memory in this linear recurrence is $\binom{n}{2}$.

By writing out the matrix representing this linear recurrence explicitly, and then row reducing, the authors of \cite{flores2018growth} are able to produce an explicit $n+1 \times n+1$ matrix with entries depending on $t$ whose determinant is equal to $\frac{1}{g_M(t)}$.

Asymptotic Growth Rate of the Braid Monoid

The growth rate of a monoid $M$ is given by $$ \rho_M = \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \frac{|M_k|}{|M_{k-1}|} $$

The authors of \cite{flores2018growth} then use this linear recurrence to obtain asymptotics about the the number of braids with $k$ twists.

Let $M_k(n)$ be the elements of the $n$ strand braid monoid $B_n$ with length exactly $k$. As above, we will want to consider sets of the form $$ M^{(i)}_k(n) = \{b \in M_k(n) :\sigma_i \prec b \text{ and } \sigma_{i+1}, \dots, \sigma_n \not \prec b\} $$

The interesting thing about these sets is that they stabilize as $n$ goes to infinity, i.e. there is a set $M^i_k(\infty)$ so that for all $n$ large enough, $M^{(i)}_k(n) = M^{i}_k(\infty)$. This can be seen because if we require that $\sigma_i$ appear in a representation for $b$, and if $\sigma_j$ appeared in $b$ for $j$ large enough, then we would be able to find a lexicographically larger representation for $b$.

It turns out that the sets $M^i_k(\infty)$ can be thought of as subsets of an infinite braid monoid. Specially, let $B_{\infty}$ be the braid monoid on infinitely many strands, or else, the inverse limit of all braid monoids under the obvious inclusions. Then $$ M^i_k(\infty) = {b \in B_{\infty} : |b| = k, \sigma_i \prec b, \text{ and } \sigma_{i+1}, \sigma_{i+2}, \dots \not \prec b} $$

The authors use some analysis results to show that for any $i$, $$ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} \rho_{B_n} = \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} \frac{|M^i_k(\infty)|}{|M^i_{k+1}(\infty)|} $$ That is, rather than considering the growth rates for all of the braid monoids separately, it is sufficient to consider this growth rate associateed with this infinite braid monoid.

Moreover, we have a recurrence relation on the sizes of $M^i_{k+1}(\infty)$. $$|M_{k}^{i+1}(\infty)| - |M_{k}^{i}(\infty)| = \sum_{\ell=i}^{\infty} (-1)^{\ell - i}(\infty)|M_{k - \binom{\ell-i+2}{2}}^{\ell+1}(\infty)|$$

where we note that this sum is in fact finite, since for $\ell$ large enough, the summands become 0.

Finally, the authors consider the generating function $$ \zeta_{0}(t) = \sum_{\ell = 0}^{\infty} |M_{\ell}^{1}(\infty)| t^{\ell} $$

They show that this is in fact a root of a bivariate generating function known as the partial theta function: $$ \theta(x, y) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty y^{\binom{k}{2}} x^k $$ and $$ \theta(\zeta_0(t), t) = 0 $$

From this, and some ideas in analysis, this turns out to imply that $$ \lim_{\ell\rightarrow \infty} \frac{|M_{\ell}^{1}(\infty)|}{|M_{\ell-1}^1(\infty)} = 3.233\dots $$ Giving a complete solution to this problem.

Simple Braid Generators

We say above that if we measure the length of an element in $B_n$ with respect to the Artin generators, we cannot obtain especially efficient codes. This makes some sense: suppose that $\sigma_1 = \phi(x)$ for some $x \in B$. If $y \in B$, and $\phi(y)$ does not involve either $\sigma_1$ or $\sigma_2$, then $\phi(y)$ will commute with $\phi(x)$, meaning that our code will not be injective. In general, if the codewords are all very short, then they must all lie in $B_n$ where $n$ is small.

In some senses, the Artin generators measure how much time it takes to generate a braid if we are only allowed to twist one pair of adjacent strands at a time. On the other hand, we might be more interested in the `space’ complexity of a braid, namely, how long do the strands need to be in order to produce enough codewords.

This is to some extent captured by the simple braid generators, which are those elements in the positive braid monoid where no two strands cross more than once. An algorithm for computing the growth function of the positive braid monoid relative to the simple braids is described in \cite{GEBHARDT2013232}.

In particular, the results of this paper imply that the number of braids in $B_n$ which can be written as the product of $k$ simple braids grows like $f(n)^{k}$. We would be interested in this case in obtaining a lower bound of the form $f(n) =\Omega(n)$.

\bibliographystyle{plain} \bibliography{braid}